This article first appeared in the on-line forum, Redcoat Images, edited by Gregory Urwin

In May of 1783 Samuel Jan Holland, Surveyor General of Quebec and the Northern District of North America, sent his Deputy Surveyor James Peachey on an assignment to lay out lots of land along the Niagara River and the north shore of Lake Ontario. They were to be assigned to members of the recently disbanded Loyalist regiments which had operated from Canada throughout the American Revolution and to other refugees who had fled to the area from the rebellious colonies. From May until November of 1784 Peachey was involved in planning settlements along the west bank of the Niagara River, at Cataraqui (now Kingston, Ontario) and Adolphustown and Fredericksburg Townships (on the north shore of Lake Ontario near present-day Napanee, Ontario). While on assignment, Peachey painted a number of watercolours which are now in the collection of the Public Archives of Canada and other institutions in Canada and the UK. These watercolours are a unique glimpse into the lives and material culture of the Loyalist refugees who settled in Canada in the late 18th Century.

The Dictionary of Canadian Biography gives considerable information on Peachey’s career. Little is known of his early life – he first appears in the records in 1773 or 1774 when he was employed in Holland’s office in Boston. After spending a few years in London he travelled again to America in 1780 where he spent some time in Quebec working for Governor Frederick Haldimand as a “draughtsman”. By 1783 he was again working for Holland and began his assignment in Upper Canada.

Peachey produced a series of paintings in 1783 and 1784 that are now in the Public Archives of Canada. They may have been intended as illustrations for a publication of large-scale plans of the St Lawrence Valley which never materialized. In 1785 he produced a second series of watercolours, possibly commissioned by Governor Haldimand, which is now dispersed in various collections.

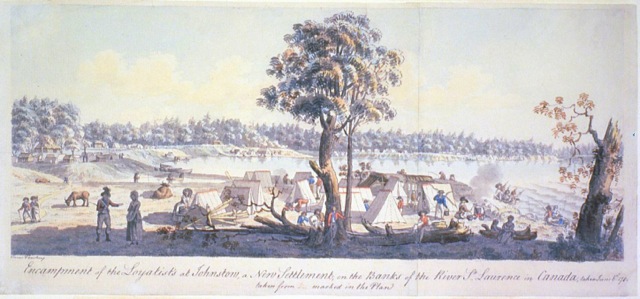

Peachey’s watercolours provide a valuable contemporary visual record of the British presence in Canada during the Revolution. Of particular interest is his painting “Encampment of the Loyalists at Johnstown, 1784” which gives a rare view of the uniforms and equipment of a Loyalist regiment from the period, the King’s Royal Regiment of New York (KRRNY). It is now in the collection of the Public Archives of Canada in Ottawa (C-002001). Peachey painted the scene on June 6 1784 – the full title being “Encampment of the Loyalists at Johnstown, a New Settlement, on the Banks of the River St. Laurence in Canada” (Figure 1).

The KRRNY was raised in Montreal on June 19 1776 by Sir John Johnson, 2nd Baronet of New York, son of the noted Sir William Johnson, 1st Baronet. Sir John had fled his Mohawk Valley estate in New York with a number of loyalist supporters to escape mistreatment at the hands of local rebels. Eventually Johnson raised two battalions which participated in a number of campaigns during the Revolution, notably the St. Leger expedition to the Mohawk Valley in 1777 where the regiment took part in the Battle of Oriskany on August 6. During the rest of the war the KRRNY was engaged in destructive punitive raids into their former communities in the Mohawk Valley. When the Revolution ended in 1783 the regiment was disbanded and resettled along the north shores of Lake Ontario and the St Lawrence River near Cornwall and Napanee, Ontario.

Peachey’s painting portrays the settlement of disbanded troops from two companies of the KRRNY and miscellaneous other loyalists at what was designated Royal Township No.2 and later became known as Cornwall. The two companies were Captain Samuel Anderson’s Light Infantry Company and Captain Patrick Daly’s Line Infantry Company.

The soldier leaning against the tree in the centre of the painting is wearing a red waistcoat indicating that he is one of Anderson’s Light Bobs. The commissioned officer talking to the lady left of centre is in a white waistcoat, indicating he is a line officer. As such, he is one of three individuals – Captain Daly himself, or perhaps Ensign John Connolly. Unfortunately, the company’s 1Lieutenant has not been identified.

Peachey’s watercolour gives some tantalizing details of the uniforms and camp life of the loyalist refugees. The KRRNY officer in the left foreground wears a red jacket with blue facings and a white waistcoat and breeches. He appears to be wearing short black gaiters over white stockings, and wears a wide-brimmed black hat with a black plume. He has a white sword belt over his right shoulder and is carrying a sword or cane under his right arm. (Figure 2)

Other figures elsewhere in the picture depict soldiers in short red jackets or wearing only red waistcoats and all wearing wide-brimmed black hats. They are housed in canvas wedge tents trimmed in red that are scattered about the camp in a distinctly un-military fashion. The soldiers and their camp followers are engaged in a number of activities including cooking, fishing , blade sharpening, etc. (Figure 3) (Figure 4)The identity of the blue-jacketed men is not clear – they may be sailors or bateaux-men judging by their uniform appearance, or they may be unincorporated loyalist civilians.

The Canadian War Museum in Ottawa has in its collection the remarkably well-preserved uniform of an officer of the King’s Royal Regiment of New York which belonged to Lieutenant Jeremiah French, who was born in Connecticut in 1743. Before the rebellion, French was a farmer and landowner of substantial means living in Manchester, Charlotte County, New York. He was jailed in Connecticut for loyalism and escaped from the Hartford jail in April 1777. By July 15, French had joined Burgoyne’s expedition and was returned as captain of the 4th company of Lieutenant-Colonel John Peters’ newly-established regiment, the Queen’s Loyal Rangers (QLR). It is very likely that French led his company on the subsidiary expedition to Bennington and was engaged in the disastrous action of August 16 at the Walloomscoick River in which the QLR lost 200 killed, wounded and taken.

Peters was embittered by these losses as his very promising battalion had been shattered, and, despite great efforts, he was unable to recover strength before the surrender of Burgoyne’s army, although French’s brother Gershom had arrived at the army’s main camp on the same day as the Walloomscoick battle with fifty-four men.

The brothers went to Canada after the surrender and remained in the QLR without incident until part way through 1780. Perhaps unwittingly they upset Lieutenant-Colonel Peters, culminating in a court martial in which Peters pressed many charges, all of which were dismissed by the officers of the court as frivolous and without foundation. The brothers were exonerated of all charges, but, of course could not continue in the QLR.

Ultimately, Jeremiah found himself in the 2nd battalion of the KRRNY as a lieutenant in Captain George Singleton’s Light Company which was stationed at Oswego. Jeremiah very likely participated in the last raid into the Mohawk Valley in July 1782 led by the Mohawk war captain, Joseph Brant.

In 1784, after the war, French settled with his wife and three daughters in Royal Township No.2 among the men of the 1st battalion. In 1792, he was elected the member for the District of Stormont in the first parliament of the new province of Upper Canada, and the next year was also serving as a magistrate.

French’s uniform consists of a short jacket or “coatee” of red wool with dark blue wool facings, a red wool waistcoat, a white wool waistcoat and a pair of white wool breeches. Some members of the re-created KRRNY had an opportunity to examine and photograph the garments in detail and learned many fascinating details about their construction.

The full uniform is shown in Figure 5. The body of the coatee is made of red melton wool lined with a lighter-weight white twill-woven wool. The facings are dark blue melton wool. The buttons are gilt metal formed over bone and embossed with the cipher KRR surrounded by a laurel wreath surmounted by a crown with the words “NEW YORK” underneath. (Figure 6) (Figure 7)The buttons are attached in groups of two on the lapels, cuffs and pocket flaps, and the buttonholes are trimmed with gold lace. There are two gold epaulettes which, as per the Royal Clothing Warrant of 1768, reflect Lt. French’s rank in a flank company. The short jacket and red waistcoat reflect typical British light infantry uniforms as outlined in the Light Infantry Regulations of 1771.

Figure 8 shows a back view of the coatee. There is a vent at the centre back seam and two pleated vents on either side of the centre back. The side vents are decorated with three gilt KRR buttons. There are two diagonally-placed false pocket flaps with scalloped edges adorned with gilt KRR buttons grouped in twos. The white turnbacks on the front edges are decorated with hearts in blue wool outlined with thin gold lace.

Figures 9 and 10 show details of the coatee facings. Figure 9 shows one of the cuffs which is approximately 3 ¼ inches wide and formed from a single layer of dark blue wool with a narrow hem turned under at the outer edge and stitched down.

Figure 10 shows a detail where the lapel and falling collar are joined together by a single button, with buttonholes trimmed with gold lace. The lapels are 2 ⅝ inches wide. Both collar and lapels are backed with red cloth. The edges of the wool fabric forming the collar and lapels are left raw and un-hemmed.

Figure 11 shows a view of the epaulette attached at the shoulder with a single plain gilt button. The layers of the collar are basted together at the edge and neck seams with dark blue thread. The buttonholes themselves are very crudely stitched with blue thread.

The epaulette is shown in detail in figure 12.

Figure 13 shows details of the interior construction of the coatee. The body is lined in white twill-woven wool with the arms lined in white linen. Although the decorative pocket flaps on the front of the coatee are non-functional, two large pockets are constructed in the interior lining. The lining fabric is turned under at all edges with a narrow seam but the wool fabric of the coat itself is raw and un-hemmed.

Lt. French’s uniform has two waistcoats – one in red melton wool (Figure 14) and one in white

(Figure 15). The red waistcoat is trimmed down the front with narrow gold lace accenting the buttons, buttonholes and pocket flaps. The gilt metal buttons bear smaller versions of the KRR cipher seen on the uniform coatee. The white waistcoat has no lace adornment. The red waistcoat is cut square around the waist along the bottom, whereas the white garment drops below the waist with swept back edges at the centre front and what appear to have been tabs (now missing) below the waist on the back. Both waistcoats have two working pockets concealed by upward-opening appliquéd pocket flaps. The buttonholes and pocket flaps are very finely worked and top-stitched

(Figure 16). Both waistcoats are lined with light-weight twill-woven wool.

A pair of white wool breeches belonging to Lt. French also survives – they are shown from the front (Figure 17) and back (Figure 18). The original buttons have not survived. They are made with a fall-front typical of the late 18th Century. An interesting detail of the breeches is the alteration done to the waist – it appears to have been let out at some point by adding extra fabric to the waistband and two small triangular wool pieces to the seat. It is possible that the wearer had the garments altered due to weight gain. The fabric for the alterations appears to have been taken from the back of the white waistcoat, which is made of the same wool as the breeches. As shown in

Figure 19 and Figure 20, the tabs from the back panels of the waistcoat have been cut off at the waist where they would not be visible while wearing the coatee, apparently to provide fabric to alter the breeches. The red waistcoat also shows evidence of alterations to accommodate weight gain – the centre-back seam has been opened and fastened with woven ties to allow it to expand

It is not often that one gets an opportunity to examine historic clothing like this in such detail; the French uniform provides some fascinating insight into the construction of Revolutionary War military garments. The combination of the surviving uniform and a contemporary watercolour of the regiment’s encampment gives a unique view of the loyalist soldiers of the American Revolution who became some of the earliest European settlers in what is now the province of Ontario.

Eric Lorenzen

(with biographical information on Lt. French by Gavin Watt, photos by Jeff Paine)